When a pharmacist hands you a pill bottle labeled with a generic name instead of the brand you asked for, it’s not just a convenience-it’s a financial decision that ripples through the entire system. You might think you’re saving money. The pharmacy might think they’re getting paid fairly. But behind the scenes, the way pharmacies get reimbursed for those generics is rigged in ways that often hurt both the pharmacist and the patient.

How Pharmacies Get Paid for Generics

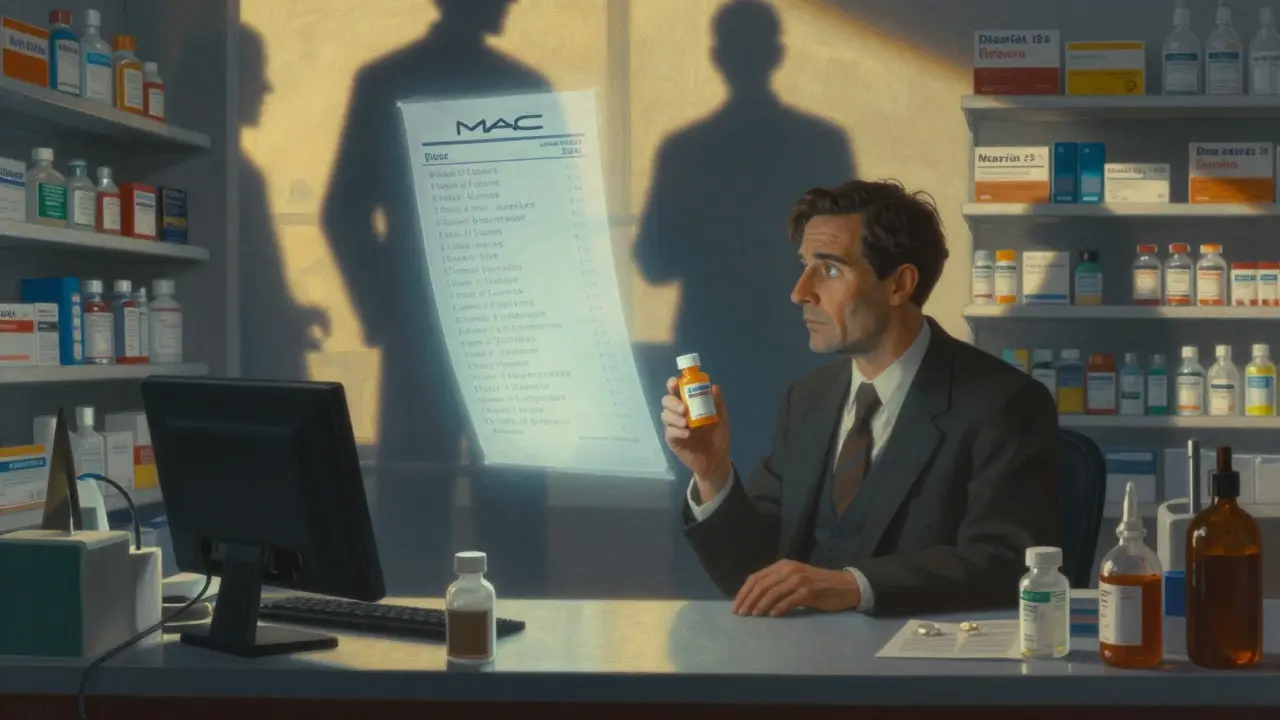

Pharmacies don’t just get paid what they pay for the drug. They get reimbursed based on complex formulas set by Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs), insurers, and government programs. The two main models are cost-plus and Maximum Allowable Cost (MAC).

Cost-plus reimbursement means the pharmacy gets a fixed percentage above what they paid for the drug, plus a flat dispensing fee. It sounds fair-until you realize that for generics, the acquisition cost is often dirt cheap. A 30-day supply of lisinopril might cost the pharmacy $1.20. If the cost-plus rate is 15%, they get $0.18 on top of that. Add a $4 dispensing fee, and they’re making $4.18 per script. That’s barely enough to cover rent, staff wages, and utilities.

MAC lists are worse. These are secret price caps set by PBMs for generic drugs. The catch? PBMs don’t always tell pharmacies what the MAC is until after they’ve filled the prescription. So a pharmacy might buy a bottle of metformin for $1.50, only to find out the MAC is $1.80. They pocket $0.30. But if the MAC is set at $1.20? They lose $0.30 on that script. And they’re not allowed to tell the patient.

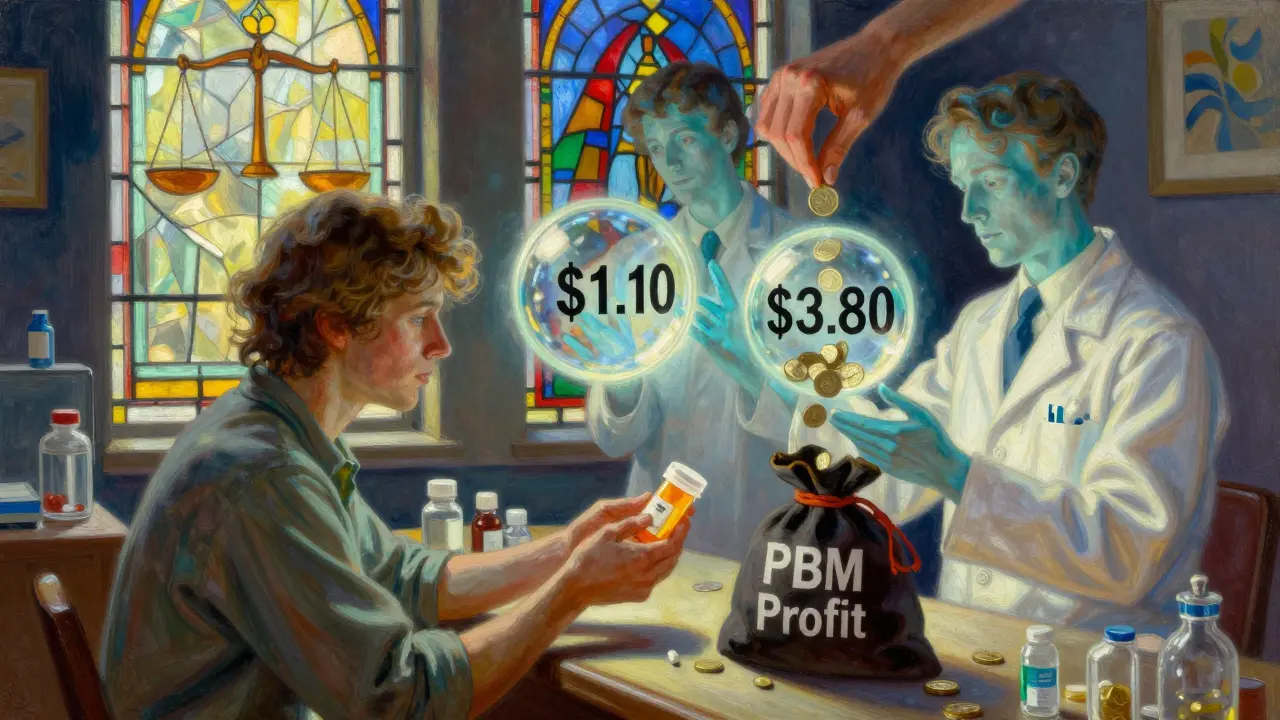

Why PBMs Push Higher-Priced Generics

Here’s the twist: PBMs make the most money when they pay pharmacies less than they charge insurers. This is called spread pricing. And they’ve figured out how to maximize it with generics.

Let’s say there are two versions of the same generic drug: one made by a small manufacturer that sells for $1.10, and another made by a big company that sells for $3.80. Both are equally effective. The PBM negotiates a $1.00 acquisition price from the cheaper maker, but sets the MAC at $3.75 for the expensive one. They charge the insurer $3.75, pay the pharmacy $1.00, and pocket $2.75. That’s a 275% profit margin on a single pill bottle.

Studies show that in the same therapeutic class, some generics are priced over 20 times higher than their cheaper alternatives-yet they’re still the ones getting dispensed. Why? Because PBMs steer prescriptions toward those higher-priced generics. Pharmacies, especially independents, have no power to push back. If they refuse to fill the expensive version, they risk being dropped from the PBM network.

What Happens to Pharmacies When Margins Collapse

Generic drugs make up over 90% of prescriptions filled in the U.S. today. That’s good for patients and good for the health system-except when pharmacies can’t make money on them.

On average, pharmacies make a 42.7% gross margin on generics. Sounds great, right? But that number hides a brutal reality: most of that margin comes from a handful of high-margin drugs. For the 80% of generics that are low-cost, the margin is often below 5%. Many pharmacies are running on razor-thin profits, if they’re profitable at all.

Between 2018 and 2022, more than 3,000 independent pharmacies closed. Why? Because they couldn’t survive under reimbursement rates that didn’t cover their costs. Big chains like CVS and Walgreens can absorb losses on generics because they make money elsewhere-on clinics, on insurance plans, on PBM contracts. Independent pharmacists can’t. They’re caught between PBMs demanding lower prices and patients expecting low copays.

Therapeutic Substitution: The Real Savings Opportunity

Most people think generic substitution means swapping one brand for its generic twin. But the biggest savings come from therapeutic substitution-switching a brand-name drug for a different generic drug in the same class that’s even cheaper.

For example, instead of prescribing a $120 brand-name statin, a doctor could switch to a generic statin that costs $5. That’s a 95% drop in cost. The Congressional Budget Office estimated that in 2007, switching just seven classes of brand-name drugs to cheaper generics could have saved $4 billion. But that rarely happens. Why? Because PBMs don’t incentivize it. They’re not paid based on total cost savings-they’re paid based on how much they can spread between what they pay the pharmacy and what they charge the insurer.

Doctors often don’t know which generics are cheapest. Pharmacists can’t recommend alternatives without prior authorization. And insurers don’t push for it because they’re locked into PBM contracts that don’t reward lower overall spending.

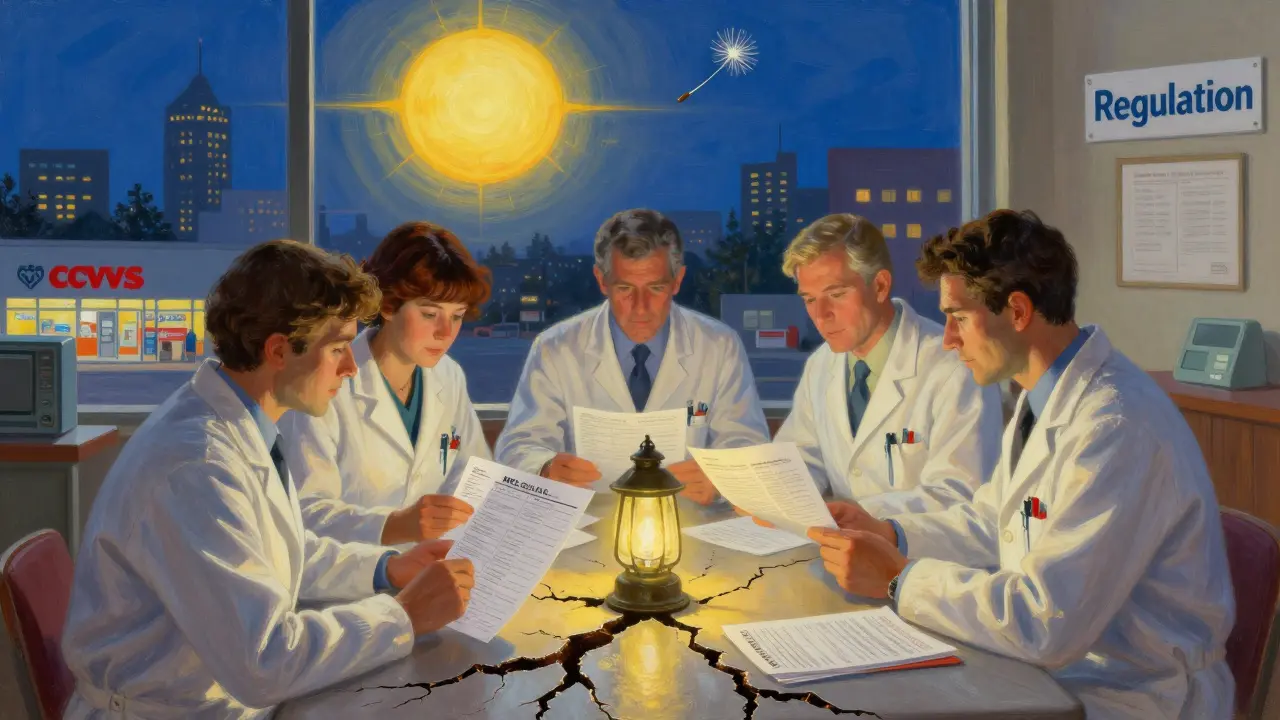

Regulatory Crackdowns Are Starting

For years, PBMs operated in the dark. MAC lists were secret. Spread pricing was hidden. Pharmacies had no way to challenge it.

Now, things are changing. The Federal Trade Commission launched investigations in 2023 into PBM pricing practices. States like Minnesota, California, and New York have created Prescription Drug Affordability Boards that set Upper Payment Limits-essentially caps on what PBMs can charge for certain drugs. The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 forced Medicare Part D to disclose pricing details, and that transparency is starting to spill over into commercial insurance.

Some PBMs are now required to disclose MAC prices to pharmacies before dispensing. Others are being forced to pass rebates directly to patients. It’s slow, but it’s moving.

What Patients and Pharmacists Can Do

Patients: Always ask, “Is there a cheaper generic option?” Don’t assume the first one they give you is the cheapest. Ask the pharmacist to check. Many times, switching to a different generic version can cut your copay in half.

Pharmacists: Document every time you’re forced to dispense a higher-priced generic because the PBM won’t let you substitute. Report it to your state pharmacy board. Join advocacy groups like the National Community Pharmacists Association. Your voice matters.

There’s no magic fix. But the system isn’t broken beyond repair. It’s just designed to benefit a few players at the expense of everyone else. Change is coming-not because it’s fair, but because it’s no longer sustainable.

Comments

Jerry Rodrigues

19 January 2026Been a pharmacist for 12 years. Saw this happen slow then fast. One day you’re making $5 on a script, next day you’re losing $1.50. No warning. No appeal. Just another MAC update that kills you quietly.

Independent pharmacies aren’t dying because they’re bad at business. They’re dying because the system was built to eat them alive.

Amber Lane

20 January 2026My grandma’s blood pressure med went from $4 to $12 copay last month. She cried. I called the pharmacy. They said the PBM changed the MAC. They couldn’t tell her why. That’s not healthcare. That’s gambling.

Glenda Marínez Granados

21 January 2026So PBMs are the middlemen who profit from making sure the middleman gets screwed? Genius. I’m starting a cult. We worship the pharmacist who still smiles after a 12-hour shift. 🙏💊

Sangeeta Isaac

23 January 2026Y’all know the funniest part? The same PBMs that set these insane MACs also sell you ‘wellness programs’ and ‘cost-saving apps’ that promise to help you manage your meds. Like, yeah, thanks for stealing my pharmacist’s soul and then selling me a $9.99/month app that tells me to drink water.

It’s not a healthcare system. It’s a horror show with a LinkedIn page.

Stephen Rock

24 January 2026Generic substitution is just capitalism with a Band-Aid. You think you’re saving money but you’re just funding a black box that turns $1 pills into $40 profit opportunities for CEOs who’ve never held a prescription bottle.

And the worst part? The pharmacists who know all this? They’re too tired to fight back. They’re just trying to make it to 6 PM without crying in the back room.

Barbara Mahone

24 January 2026My mother worked as a pharmacy technician for 27 years. She never complained. But last Christmas, she said, ‘I used to feel like I helped people. Now I feel like I’m a pawn in a game no one understands.’

That’s when I realized this isn’t about drugs. It’s about dignity.

lokesh prasanth

26 January 2026why dont u just use herbal meds bro its cheaper and no pmb needed

Alex Carletti Gouvea

27 January 2026They call it ‘generic substitution’ like it’s some noble act. It’s corporate theft disguised as efficiency. We’re not talking about aspirin here-we’re talking about insulin, heart meds, antidepressants.

And the worst part? The people who get hurt the most are the ones who can’t afford to shop around. They’re stuck with whatever the PBM decides to shove into their bottle.

This isn’t capitalism. It’s feudalism with a pharmacy counter.

MARILYN ONEILL

28 January 2026People don’t get it. The PBM doesn’t care if you live or die. They care if you pay more than the next guy. If your drug costs $1.20 and they charge $3.75? Congrats. You’re a revenue stream.

They’re not fixing healthcare. They’re monetizing desperation.

Andrew Rinaldi

29 January 2026There’s a deeper question here: Why do we let third parties control the most intimate part of someone’s health? The doctor prescribes. The patient takes. The pharmacy dispenses. That’s the triangle.

Now we’ve added a fourth player-the PBM-who never meets the patient, never sees the pain, and still gets to decide if you can afford your life.

It’s not broken. It was designed this way.

shubham rathee

31 January 2026you ever wonder why all the big pharmacy chains are owned by the same people who run the PBMs? its not a coincidence its a cartel

they want you to think its competition but its all one big machine grinding down small shops

the government knows but they take the money so they look away

Jerry Rodrigues

31 January 2026Replying to the guy who said herbal meds. That’s not a solution. That’s dangerous. Some people need real medicine. Not tea.

And if you think the system’s broken because of ‘big pharma’-you’re missing the real villain. It’s the middlemen. The ones who never touch a pill but get rich off the suffering.

Dee Monroe

31 January 2026I used to think pharmacies were just places you went to get pills. Now I see them as quiet heroes holding back a flood.

Every time a pharmacist swallows their pride and fills a script they lose money on, they’re choosing compassion over survival.

They’re not just filling prescriptions-they’re keeping families together, one $0.30 loss at a time.

I don’t know how to fix this. But I know we owe them more than silence.

Next time you’re at the counter, look them in the eye. Say thank you. Not because they’re nice. But because they’re still here.

And that’s not just service. That’s resistance.

Samuel Mendoza

1 February 2026Wait so you’re telling me the system isn’t perfect? Shocking. I thought the free market always wins. Guess I was wrong. Maybe we should just let the rich buy their meds and the rest of us die quietly. That’s more efficient.

Stephen Rock

3 February 2026Replying to Dee Monroe: You’re right. They’re heroes. But heroes don’t get pensions. They get fired when their profit margin dips below 3%.

And when the last independent pharmacy closes? Who’s gonna be there to answer your question about drug interactions? A robot at CVS? A PBM algorithm that only speaks in copay numbers?