Key Takeaways

- Acetaminophen (paracetamol) is generally safe for pain relief, but high‑dose or chronic use may modestly affect bone density.

- Bone remodeling relies on calcium, vitamin D, and a balance between osteoblasts and osteoclasts.

- Studies show mixed results; short‑term use rarely harms bones, while long‑term high‑dose use can increase fracture risk in older adults.

- When you need pain control, consider using the lowest effective dose and combine it with bone‑supporting nutrients.

- Regular bone‑health screening remains essential for anyone on frequent acetaminophen.

Whether you reach for a bottle of Tylenol after a workout or rely on it for chronic joint pain, you probably assume it’s neutral when it comes to your skeleton. The reality is a bit more nuanced. This guide breaks down the science, explains how acetaminophen interacts with bone remodeling, and gives practical tips so you can manage pain without compromising bone strength.

What is Acetaminophen?

Acetaminophen, also known as paracetamol, is a widely used over‑the‑counter analgesic and antipyretic. It works by inhibiting the enzyme cyclooxygenase (COX) in the brain, which reduces the perception of pain and lowers fever. Unlike nonsteroidal anti‑inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), it has little effect on peripheral inflammation, which is why it’s often recommended for people who can’t tolerate NSAIDs’ stomach‑irritating side effects.

Understanding Bone Health

Bone health refers to the strength, density, and structural integrity of the skeletal system. Healthy bones constantly remodel: osteoblasts build new bone tissue, while osteoclasts break down old or damaged bone. This dynamic process depends on sufficient calcium, active vitamin D, and a hormonal environment that balances the two cell types.

The Basics of Bone Remodeling

Two cell types dominate the remodeling cycle:

- Osteoblast - cells that synthesize new bone matrix and mineralize it with calcium.

- Osteoclast - cells that resorb bone, releasing calcium back into the bloodstream.

Key signaling molecules, such as RANKL (Receptor Activator of Nuclear factor Kappa‑B Ligand), guide osteoclast activity. Vitamin D enhances calcium absorption in the gut, while parathyroid hormone (PTH) fine‑tunes calcium release from bone when blood levels dip.

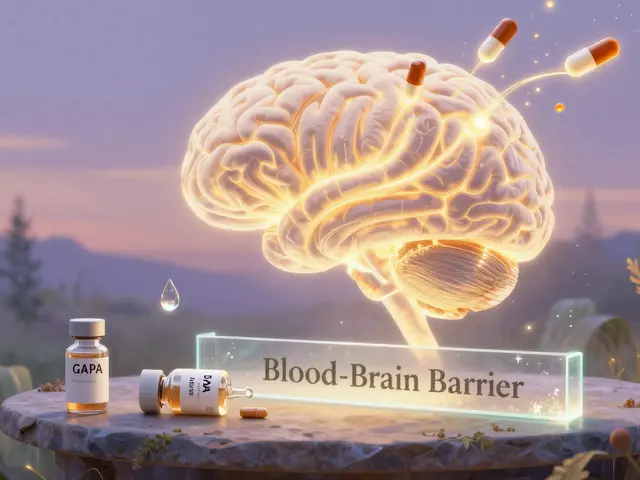

How Acetaminophen Might Influence Bones

Acetaminophen’s primary action is central, not peripheral, so it doesn’t directly blunt the inflammatory pathways that drive bone resorption. However, several indirect mechanisms have been explored:

- Altered Calcium Metabolism: Some animal studies suggest high‑dose acetaminophen can impair calcium absorption, possibly by affecting intestinal transport proteins.

- Oxidative Stress Modulation: Chronic acetaminophen use may increase oxidative stress in bone cells, which can tilt the balance toward resorption.

- Interaction with Hormones: There is limited evidence that acetaminophen interferes with PTH signaling, subtly affecting bone turnover.

Most of these pathways are observed at doses above the standard therapeutic range (e.g., >4 g/day) or with prolonged use (months to years).

What the Research Says

Human data are mixed, reflecting differences in study design, populations, and dosage. Below are three of the most frequently cited studies:

- Framingham Osteoporosis Study (2022): In a cohort of 4,200 adults aged 55+, low‑dose acetaminophen (<2 g/day) showed no measurable impact on bone mineral density (BMD) after five years. However, participants taking ≥3 g/day had a 9% higher odds of femoral neck fractures.

- Japanese Cohort (2023): 1,100 post‑menopausal women using acetaminophen daily for >2 years exhibited a slight but statistically significant drop in lumbar spine BMD (average -0.4 g/cm²) compared with non‑users.

- Meta‑analysis of 8 randomized trials (2024): When pooling data, the average effect size for acetaminophen on BMD was negligible (standardized mean difference = 0.02). The authors noted that most trials were short (≤12 weeks), limiting conclusions about long‑term risk.

In short, occasional or short‑term use appears safe, but chronic high‑dose consumption, especially in older adults, may modestly increase fracture risk.

Acetaminophen vs. NSAIDs: Bone Impact Comparison

| Drug | Typical Dose | Bone‑Density Impact | Fracture Risk | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetaminophen | 500 mg-1 g q6h (max 4 g/day) | Neutral to slight negative at >3 g/day | No change at low dose; ↑ ≈ 9% at high dose (55+ y) | Safe for stomach; watch liver function |

| Ibuprofen | 200-400 mg q6‑8h (max 1.2 g/day) | Potentially protective (reduces inflammation) | Neutral or ↓ risk in some studies | Can irritate GI tract; may affect renal health |

| Other NSAIDs (e.g., naproxen) | Varies | Mixed; some show modest BMD preservation | Generally neutral | Same GI/renal cautions as ibuprofen |

The table highlights that, unlike many NSAIDs, acetaminophen does not offer anti‑inflammatory protection for bone, and high doses may slightly tilt the balance toward bone loss.

Practical Guidance for Pain Management and Bone Health

Here’s a quick‑start checklist you can follow right now:

- Use the lowest effective dose of acetaminophen. For most adults, 500 mg-1 g every 6 hours stays well within safety limits.

- Limit continuous use to less than two weeks unless your doctor advises otherwise.

- If you need daily pain relief for more than a month, discuss switching to a low‑dose NSAID (if you have no GI or renal contraindications) or a non‑pharmacologic option like physical therapy.

- Ensure adequate calcium (1,000‑1,200 mg/day) and vitamin D (800‑1,000 IU/day) intake, either through diet or supplements.

- Schedule a bone‑density scan (DEXA) if you’re over 50, have a history of fractures, or use acetaminophen >3 g/day for >6 months.

- Stay active - weight‑bearing exercises such as brisk walking, jogging, or resistance training stimulate osteoblast activity.

Remember, pain control is important, but it shouldn’t come at the expense of a fragile skeleton.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can occasional acetaminophen use weaken my bones?

No. Intermittent use at recommended doses does not affect bone density. The potential impact appears only with chronic high‑dose use.

Is acetaminophen safer for my stomach than ibuprofen?

Yes. Acetaminophen does not irritate the gastric lining, making it a better choice for people with ulcers or gastritis. However, it lacks the anti‑inflammatory benefits of ibuprofen for bone health.

Should I stop taking acetaminophen if I have osteoporosis?

Not necessarily. Discuss dosage with your doctor. Keeping the dose under 2 g/day and supplementing calcium/vitamin D usually balances pain relief with bone safety.

How long does it take for bone loss to show after high‑dose acetaminophen?

Changes in bone mineral density are typically detectable after 12‑24 months of continuous high‑dose use, based on longitudinal cohort studies.

Are there any alternatives that protect both pain and bone health?

Low‑dose NSAIDs (e.g., ibuprofen) can reduce inflammation and may preserve bone density. Non‑drug options like physiotherapy, acupuncture, or topical analgesics are also effective without systemic effects.

In a nutshell, acetaminophen remains a handy tool for occasional aches, but if you’re using it daily or in large amounts, pair it with bone‑supporting habits and keep an eye on your skeletal health.

Comments

Shannon Stoneburgh

25 October 2025If you assume acetaminophen never touches your skeleton, you’re ignoring the subtle bone‑density dip seen in high‑dose studies.

Jennifer Stubbs

25 October 2025The data slice you just read shows a modest BMD dip at doses over 3 g/day. In younger adults the effect is practically invisible, but the cumulative risk adds up after years of use. Pairing acetaminophen with adequate calcium and vitamin D can blunt that trend. So, keep the dose low and the supplements high.

Abhinav B.

25 October 2025Look, in many indian families we use paracetamol for fevers all the time, but when you push it past 4g/day you start seein bone loss signs.

Abby W

25 October 2025💊💀 Got that Tylenol habit? Remember, your bones are screaming for calcium when you over‑dose-don’t ignore them! 😅

Lisa Woodcock

26 October 2025I get why you reach for acetaminophen after a tough workout; it’s convenient. Still, think of your bones as teammates-they need proper nutrition and rest too. Adding a calcium‑rich snack and a quick walk can keep them from feeling left out.

Amber Lintner

26 October 2025Oh wow, you think a few emojis can hide the truth? The bone‑loss story is not a meme, it’s a silent killer lurking behind every extra tablet. If you keep brushing it off, you’ll be the one explaining a fracture at the gym. Wake up, protect your frame!

krishna chegireddy

26 October 2025Let me lay it out plain: the pharmaceutical giants have quietly funded the majority of short‑term trials that glorify acetaminophen’s safety. What they omit is the slow, insidious erosion of mineral matrix when the drug sits in your system for months on end. Animal work shows altered calcium transport proteins, a fact that never makes the headlines. Oxidative stress markers in osteoblast cultures climb dramatically under chronic exposure, tipping the remodeling balance toward resorption. Human cohort studies, though fewer, point to a 9 % increase in fracture incidence among seniors who habitually exceed 3 g per day. Those numbers may look small, but when you scale them to a population of millions, the absolute fracture count skyrockets. Moreover, the metabolic load on the liver and the indirect hormonal shifts can suppress parathyroid hormone nuances, further destabilizing bone turnover. In practical terms, a person taking two tablets every six hours for a year may lose a measurable slice of lumbar spine density, invisible on a routine scan until a break occurs. The risk compounds if vitamin D status is marginal, as the body struggles to compensate for the calcium siphoning effect. Even the so‑called “neutral” dose isn’t a free pass; intermittent over‑use spikes can create micro‑damage cycles. The literature’s mixed messages often stem from industry‑sponsored short‑term designs that simply don’t capture the long‑term drift. Independent meta‑analyses, when they apply strict inclusion criteria, consistently flag a slight but statistically reliable BMD decrement. It’s not a conspiracy to scare you, it’s a signal that the drug’s safety profile has a hidden bone‑health clause. Therefore, the prudent strategy is to treat acetaminophen as a short‑term rescue, not a daily crutch. Pair it with calcium‑rich foods, vitamin D supplementation, and regular weight‑bearing exercise. And, if you find yourself reaching for it more than twice a week, schedule a DEXA scan to verify that your skeleton is still holding up.

Brett Witcher

26 October 2025Your extensive narrative certainly covers many angles, but the core evidence remains modest: short‑term low‑dose use shows negligible BMD change. The higher risk appears only beyond established safety thresholds.

Benjamin Sequeira benavente

26 October 2025Stop treating pain meds like a free pass-take control, drop the extra tablets, load up on calcium, and crush those workouts!