When a generic drug company wants to prove their version of a medication works just like the brand-name version, they don’t just guess. They run a crossover trial design. This isn’t just a common method-it’s the gold standard for bioequivalence studies. And if you’re wondering why so many generic drugs hit the market so quickly and cheaply, the answer starts with how these studies are built.

Why Crossover Designs Rule Bioequivalence Testing

Imagine you’re testing two painkillers: one brand-name, one generic. In a parallel study, half the people get the brand, half get the generic. Then you compare average results. Simple. But here’s the problem: people are different. One person might metabolize drugs faster than another. Age, weight, liver function-all these things affect how a drug behaves in the body. That’s noise. And noise makes it harder to tell if the two drugs are truly the same. A crossover design solves this by making each person their own control. Everyone gets both drugs-just not at the same time. First, you take Drug A (say, the brand). Then, after a break, you take Drug B (the generic). You don’t know which is which. The researchers don’t either. That’s double-blind. By comparing how your body handles Drug A versus Drug B, you remove most of the noise. Your body is the constant. Only the drug changes. This cuts the number of people needed by up to 80%. Instead of 72 volunteers for a parallel study, you might only need 24. That’s not just cheaper-it’s faster, more ethical, and more precise. The U.S. FDA and the European EMA both say this is the preferred method. In fact, 89% of all bioequivalence studies approved by the FDA in 2022 and 2023 used this design.The Standard 2×2 Crossover: AB/BA

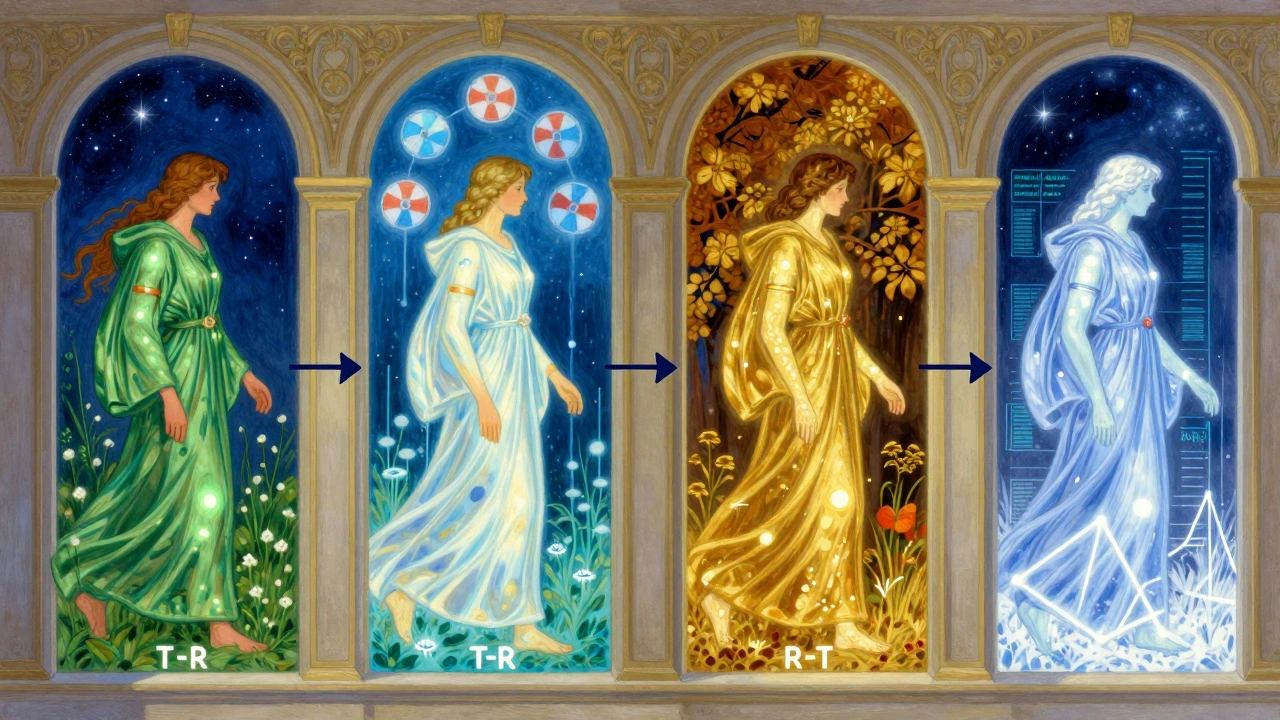

The most common setup is called the 2×2 crossover. It’s simple: two treatment periods, two sequences. - Group 1: Gets the test drug first (T), then the reference drug (R) → T-R sequence - Group 2: Gets the reference drug first (R), then the test drug (T) → R-T sequence This is often written as AB/BA, where A is the test and B is the reference. Randomization ensures both groups are balanced. The key? The washout period. Between the two doses, there’s a waiting period-usually five times the drug’s elimination half-life. Why? So the first drug is completely gone from your system before you get the second. If even a little bit of the first drug remains, it can mess up the results. That’s called a carryover effect. And it’s the #1 reason studies get rejected. For example, if a drug has a half-life of 8 hours, you need at least 40 hours between doses. For a drug like warfarin, which has a half-life of 40 hours, that’s a 7-day break. That’s why warfarin studies take longer. But it’s worth it. A 2022 case study from a clinical trial manager showed switching from a parallel to a 2×2 crossover design saved $287,000 and 8 weeks of study time.What Happens When the Drug Is Highly Variable?

Not all drugs play nice. Some-like those used for epilepsy, blood thinners, or certain antibiotics-have what’s called high intra-subject variability. That means even the same person’s body responds differently each time they take it. The coefficient of variation (CV) is over 30%. In these cases, the standard 2×2 design doesn’t cut it. Why? Because the natural variation in your body’s response swamps out the tiny differences between the brand and generic. You’d need hundreds of people to prove equivalence-and that’s not practical. Enter the replicate design. There are two types:- Partial replicate (TRR/RTR): You get the test drug once, and the reference drug twice. So: T-R-R for one group, R-T-R for the other.

- Full replicate (TRTR/RTRT): You get each drug twice: T-R-T-R for one group, R-T-R-T for the other.

Statistical Analysis: It’s Not Just Averages

You can’t just compare average blood levels. That’s where things go wrong. Bioequivalence is proven using the ratio of geometric means for two key metrics: AUC (how much drug is absorbed over time) and Cmax (the highest concentration reached). The 90% confidence interval for this ratio must fall between 80% and 125% for most drugs. But to get there, the stats model has to account for:- Sequence effect (did the order matter?)

- Period effect (did time itself affect results?)

- Treatment effect (was there a real difference between drugs?)

Washout Periods: The Silent Killer

The biggest mistake in crossover studies? Underestimating the washout. One statistician on ResearchGate shared a story where his team assumed a drug’s half-life was 12 hours. They used a 60-hour washout. Turns out, the real half-life was 18 hours. Residual drug was still in the system during the second period. The study failed. They had to restart with a 4-period replicate design. Cost: $195,000. Washout isn’t a suggestion. It’s a requirement. And it must be validated. That means either using published pharmacokinetic data or running a pilot study to confirm concentrations drop below the lower limit of quantification. Documentation matters. Regulators check it.

When Crossover Doesn’t Work

Crossover isn’t magic. It fails when the drug’s half-life is too long. Think of drugs like teriparatide (used for osteoporosis) or some long-acting injectables. If the half-life is over two weeks, a 5-half-life washout means waiting over 10 weeks between doses. No one’s going to come back for 6 visits over 6 months. It’s impractical. In those cases, parallel designs are the only option. Also, crossover doesn’t work for irreversible effects. If a drug causes permanent tissue changes-like some chemotherapy agents-you can’t give it twice. The second dose would be dangerous.What’s Changing Now?

The field is evolving. The FDA’s 2023 draft guidance now allows 3-period designs for narrow therapeutic index drugs-drugs where even tiny differences can be dangerous, like digoxin or phenytoin. The EMA’s 2024 update will make full replicate designs the preferred choice for all highly variable drugs. Adaptive designs are also rising. These let researchers re-calculate sample size halfway through the study based on early data. In 2018, only 8% of studies used this. By 2022, it jumped to 23%. That’s a big shift. And while digital health tools-like wearable sensors that track drug levels continuously-are still experimental, they could one day reduce the need for washout periods. Imagine monitoring drug concentrations in real time instead of drawing blood every few hours. That’s the future.Bottom Line: Why This Design Still Wins

Crossover designs dominate bioequivalence studies because they’re efficient, precise, and scientifically sound. They reduce variability, lower costs, and speed up generic drug approval. The FDA and EMA back them. The industry uses them. And when done right-with proper washout, solid stats, and correct design-they’re nearly flawless. But they’re not easy. They require expertise. They demand precision. And they can fail in expensive ways if corners are cut. That’s why the best companies don’t just follow the template-they understand the science behind it. If you’re working in generic drug development, this isn’t just a method. It’s your foundation.What is the main advantage of a crossover design in bioequivalence studies?

The main advantage is that each participant acts as their own control, eliminating differences between people like age, weight, or metabolism. This reduces variability and allows researchers to use far fewer participants-sometimes as few as one-sixth the number needed in a parallel study-while still getting reliable results.

What is the standard crossover design for most bioequivalence studies?

The standard design is the 2×2 crossover, also called AB/BA. Participants are split into two groups: one gets the test drug then the reference (AB), and the other gets the reference then the test (BA). A washout period of at least five half-lives separates the two treatments.

When is a replicate crossover design used?

Replicate designs (like TRR/RTR or TRTR/RTRT) are used for highly variable drugs, where the intra-subject coefficient of variation exceeds 30%. These designs allow regulators to use reference-scaled average bioequivalence (RSABE), which adjusts acceptance limits based on how variable the reference drug is, making it easier to prove equivalence without needing hundreds of participants.

What is the biggest risk in a crossover trial?

The biggest risk is carryover effect-when the first treatment still affects the body during the second treatment period. This can happen if the washout period is too short. Carryover can invalidate results and cause studies to be rejected by regulators like the FDA or EMA.

Why can’t crossover designs be used for all drugs?

Crossover designs aren’t suitable for drugs with very long half-lives (over two weeks) because the required washout period would be too long for participants to wait. They’re also not used for drugs that cause irreversible effects, like some chemotherapy agents, since giving the drug twice could be dangerous.

Regulatory trends show replicate designs are growing fast. In 2015, only 12% of highly variable drug approvals used reference-scaled methods. By 2022, that number jumped to 47%. As more complex generics enter the market, crossover designs aren’t going away-they’re getting smarter.

Comments

Dematteo Lasonya

5 December 2025Really clear breakdown. I’ve seen studies fail because someone skipped the washout and blamed the generic. It’s not the drug-it’s the design.

Jessica Baydowicz

7 December 2025This is the kind of stuff that makes me love pharmacology. No fluff, just science that saves lives and money. 🙌

zac grant

7 December 2025Replicate designs are the future. RSABE isn’t just a workaround-it’s a smarter regulatory framework for complex drugs. The FDA’s moving in the right direction.

Gareth Storer

9 December 2025So what you’re saying is, we’re trusting a bunch of pharma bros with a math trick to approve drugs that might kill people? Brilliant.

val kendra

10 December 2025Washout periods are where most teams cut corners. I’ve seen people use half-life data from a 1998 paper for a drug that got reformulated in 2020. No wonder studies fail.

Validate your PK. Don’t assume. Test it. It’s not hard, it’s just tedious.

And yes, SAS is still the boss. R is cool if you’ve got a biostatistician on speed dial.

Scott van Haastrecht

11 December 2025Of course the FDA loves this design. It’s cheaper. That’s the only reason. They don’t care if your drug’s safe-they care if it passes a spreadsheet.

Next they’ll replace blood draws with a phone app that asks you how you feel.

Libby Rees

12 December 2025The elegance of the crossover design lies in its simplicity: eliminate between-subject variability, and the signal becomes clear. It’s statistical hygiene.

Rachel Bonaparte

14 December 2025Did you know the same people who push crossover designs also lobby against mandatory transparency in clinical trials? It’s not about science-it’s about control.

They want you to trust the numbers without seeing the raw data. That’s not science. That’s corporate theater.

jagdish kumar

16 December 2025Everything has a cost. Even science.

Joe Lam

17 December 2025You’re all missing the point. This isn’t about bioequivalence-it’s about patent extensions disguised as public health. The whole system is rigged.

Generic companies don’t want to prove equivalence. They want to bypass the brand’s IP with a statistical loophole.

And you’re celebrating it like it’s progress.

Pavan Kankala

19 December 2025They’re testing drugs on people so the rich can sell cheaper pills. Meanwhile, the real problem is drug prices. This is just a distraction.

Isabelle Bujold

20 December 2025One thing people don’t talk about: the emotional toll on participants. Doing four visits over 12 weeks, fasting, getting poked repeatedly-it’s not just a number in a dataset. These are real people sacrificing their time and comfort.

And if the washout isn’t long enough? They’re exposed to a second drug before the first is fully cleared. That’s not just a statistical error-it’s a safety risk.

We need better ethics oversight, not just better stats models.

The FDA’s new 3-period guidance is a step forward, but it’s still reactive. We need proactive monitoring, not just post-hoc corrections.

And digital biomarkers? Yes. Wearables that track plasma concentrations via sweat or saliva? That’s the future. We’re decades behind where we could be.

Michael Feldstein

22 December 2025Great summary. For anyone new to this: the 2×2 crossover is the backbone of generic approval. But don’t forget-the stats are only as good as the data collection.

Missing a blood draw? Don’t toss the subject. Use mixed models with likelihood methods. It’s messy, but it preserves power.

And always, always validate your washout. A pilot PK study costs $20K. A failed Phase 3 costs $2M.

Augusta Barlow

23 December 2025They say crossover designs are efficient, but what about the people who can’t tolerate both drugs? What if the generic gives you nausea and the brand doesn’t? You’re forced to take it anyway because the protocol says so.

This isn’t science-it’s coercion wrapped in a lab coat.

And don’t get me started on how they define ‘complete washout.’ Just because the concentration is below the limit of quantification doesn’t mean the drug’s not still active.

They’re playing with human biology like it’s a video game.

Jenny Rogers

24 December 2025It is, without question, an intellectually rigorous methodology. The adherence to statistical orthodoxy, the precision of the geometric mean ratio, and the formalized constraints imposed by the 80-125% interval reflect a deep commitment to epistemic integrity.

One must, however, acknowledge the ontological limitations inherent in reducing physiological response to a univariate metric. The human organism is not a linear system. To assume otherwise is to commit a category error of the highest order.

Nevertheless, within the confines of regulatory epistemology, the crossover design remains the most defensible paradigm available.